- Home

- Charles de Lint

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Read online

Jack the Giant-Killer

Jack of Kinrowan Book 1

by

Charles de Lint

Copyright 1987 by Charles de Lint.

Smashwords Edition, License Notes:

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

For MaryAnn and Terri

And dedicated to the memory of

K.M. Briggs (1898-1980)

CONTENTS

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Red is the colour of magic in every country, and has been so from the very earliest times. The caps of fairies and musicians are well-nigh always red.

– W.B. Yeats, from Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry

Rowan and I and I am sister to the Red Man

my berries are guarded by dreamless dragons

My wood charms the spells from witches

and in the wide plain my floods quicken

– Wendlessen, from The Calendar of the Trees

Though she be but little, she is fierce.

– William Shakespeare, from A Midsummer Night's Dream

One

The reflection that looked back at her from the mirror wasn't her own. Its hair was cut short and ragged like the stubble in a cornfield. Its eye make-up was smudged and the eyes themselves were red-veined and puffy. She hadn't been crying, but oh, she'd been drinking ….

"Jacky," she mumbled to the reflection. "What've you done to yourself this time?"

Five hours ago she'd numbly watched the door of her apartment slam shut behind Will.

"You're so goddamn predictable!" he'd shouted at the end. "Nothing changes the routine. It's just night after night of burrowing away in this place. What do I have to do to drag you away from your books or that glass tit? This place is a prison, Jacky, and I'm not buying into it. Not anymore. I'm tired of going out on my own, tired of … Christ, we've got absolutely nothing in common and I don't know what I ever thought we did have."

He'd stood there, red-faced, a vein throbbing at his temple, then turned and walked out the door. She knew he wasn't coming back. And after that outburst, she didn't want him back.

There was nothing wrong with being a homebody. There was nothing wrong with not wanting – not needing – the constant jostle and noise of a party or a bar or … whatever. Maybe it was better this way. She didn't need what Will offered any more than he seemed to want what she had. So why did she feel guilty? Why did she feel so … empty? Like there was something missing.

She remembered going to the window, reaching it in time to see Will disappearing down the street. Then she'd gone into the bathroom and stood in front of the mirror looking at herself. What was missing? Could you see it by just looking at her?

Her waist-length blond hair hadn't been cut in twelve years – not since she was, God, seven. She was wearing her favorite clothes: a baggy plaid shirt and a comfortable pair of old Levi's. When she walked down the street, did people turn to look at her and maybe … laugh? Did they think she was some kind of hippie burnout, even though she'd barely been out of diapers during the sixties?

She wasn't sure what had started it, but one moment she was just standing there in front of the mirror, and the next she had a pair of scissors in her hand and the long blond tresses were falling to the floor, one after another, while she kept saying, "I'm not empty inside," over and over, trying to find some meaning in what she was doing. And when she was finished, she was more numb than when Will had walked out the door. There was a stranger staring at her out of the mirror.

She remembered fumbling with her make-up, smudging it as she put it on, smearing it some more as she knuckled her eyes. Finally she bolted from the apartment.

The October air was cooling as it got dark. The streets of Ottawa were slick from the rain that had been washing them for the better part of the afternoon. She walked aimlessly, stunned at what she had done, at how light her head felt, at the touch of the wind on her scalp.

She had gone into a bar and had a drink. Then had another. Then lost count. And now she was here in some grimy bathroom, the sound of the bar's sound system booming through the ceiling from upstairs, some strange-looking punk rocker staring back at her from the mirror, and she was too lost to do anything.

"Get out of here," she told her reflection. "Go home."

The door opened behind her and she started guiltily as a pair of young women entered the washroom. They were sleek, like Vogue models. Styled hair, high heels. They regarded her curiously, and Jacky fled their amused scrutiny, the washroom, the bar, and found herself on the streets, stumbling, because she was far from sober; cold, because she'd forgotten to bring a jacket; and empty … so empty inside.

She took Bank Street south from downtown, leaving behind the unhappy mix of old-fashioned stone buildings and new glass-and-steel office complexes – which looked more like men's cologne containers than buildings – when she walked under the Queensway overpass and into the Glebe. Here stores still fronted Bank Street, but the blocks running east and west on either side were all residential. When she crossed Lansdowne Bridge, she turned east by the Public Library, following Echo Drive down to Riverdale, crossed Riverdale and walked down Avenue Road until she eventually reached Windsor Park.

Her route took her in the opposite direction from her apartment on Ossington, but she liked the peaceful mood of the park at night. The Rideau River moved sluggishly to her left. The grass was still wet underfoot, soaking her sneakers. The brisk walk from downtown Ottawa had warmed her up so that her teeth no longer chattered. The night was quiet and she was sober enough to indulge in one of her favorite pastimes: looking in through the lit windows of the houses she passed to catch brief glimpses of other people's lives.

Other people's lives. Did other people's boyfriends leave them because they were too dull?

She'd met Will at her sister Connie's wedding three months ago. He'd been charmed then by the same things that had sent him storming out of her life earlier this evening. Then it had been "a relief to find someone who isn't just into image." A person who "valued the quiet times." Now she was boring because she wouldn't do anything. But he was the one who'd changed.

When they first met, they'd made their own good times, not needing an endless tour of parties and bars. But quiet times at home weren't enough for Will anymore, and she hadn't wanted to change. Had that really been what she'd wanted, she asked herself now, or was she just too lazy to do more?

She hadn't been able to answer that earlier, and she couldn't answer it now. How did other people deal with this kind of thing?

She looked in backyards and windows, as if expecting to find an answer there. The houses that fronted Belmont Avenue and bac

ked onto the park where she was walking were mostly brick or wood-frame, dating back to the fifties and earlier. She moved catlike in the grass beside them, not going too close to the lit windows, not even stepping into their backyards, just stealing her glimpses as she moved slowly by. Here an overhead fixture lit a huge oil painting of a Maritime fishing village, there subtle lighting gleamed on two marble statues of birds, an eagle and an owl, the light behind them hiding their features, if not their profiles, and making soft halos around their silhouettes.

She paused, smiling at the picture they made, feeling almost sober. She moved on, then tensed, hearing a sound in the distance. It was a deep-throated growl of a sound that she couldn't quite place.

She looked around the park, then to the house beside the one with the two marble birds. Its windows were dark, but she had the feeling that someone was standing there looking out at her as quietly as she was looking in. Catsoft. Silent against the rumble of sound that was getting louder, steadily approaching. For a long moment she returned the gaze of the hidden watcher. She swayed and shivered, sobriety and warmth leaving as she paused too long in one spot. Then she caught a glimpse of movement at the far end of the park.

It looked like a young boy no more than ten or twelve, judging from his size, though she knew that could be deceptive in the dark. He ran under a pool of shadows thrown by the trees near the river, came out of them again, disappeared into another splash of darkness. And then the sound was all around her. She stood stunned at its volume.

It was the roar of an engine, she realized. No. Make that engines. Her gaze was drawn back to the far end of the park where the boy had first appeared and she picked out the source of the deep-throated roaring.

One by one the Harleys came into view until there were nine of the big chopped-down machines moving down the concrete walkway that followed the river. Jacky gasped when they left the concrete. Their tires ripped up the wet sod. They were coming toward her, the thunder of their engines unbelievably loud, their riders black featureless shapes.

She stumbled backward, looking for a place to hide, and came up short against a cedar hedge. Her heart drummed a sharp tattoo in her chest. Then she saw that they weren't after her. It was the boy. She'd forgotten the boy ….

He was running across the grass now, the nine bikes following in a fanned-out half-circle, engines growling. Jacky vacillated between fear for the boy and her own panic. She shot a glance at the window of the house behind her and saw the hidden watcher clearly for a moment. A tall man standing there in the safety of his house, watching.

She turned back, saw the boy stumble, the bikers closing in. They were frightening shapes in the dim light, not quite defined. Growling beasts with shadow riders. They circled around the fallen boy, a grotesque merry-go-rounding blur with whining engine coughs in place of a calliope's music, until something snapped in Jacky.

"No!" she cried.

If the bikers could hear her above the roar of their machines, they gave no notice. Jacky ran toward them, slipping drunkenly on the grass, wondering why there weren't lights going on all up and down the block behind her, why there was only one man watching from his window, a silent shape in his dark house.

Around and around the bikers rode their machines, tightening the circumference of their circle until they finally brought their machines to skidding halts. Sod spat from their rear wheels as all nine Harleys turned to face the boy. The riders fed gas to their machines so that they lunged forward like impatient dogs hungry for the kill, held back only by the leather-gloved grips on the brake levers.

The boy rose in a crouch, speared by the beams of nine headlights. And it wasn't a boy, Jacky saw suddenly. It was a man – a little man no taller than a child, with a tuft of white hair at his chin, and more spilling out from under a red cap. He had a short wooden staff in his hand that he brandished at the bikers. His eyes glowed red in the head beams of the Harleys, like those of a fox or a cat.

She saw all this in just one moment, the space between one breath and the next, then her sneakers slipped on the wet grass underfoot and she went sprawling. Adrenaline burned through her, bringing her to her feet with a grace and speed she wouldn't have been able to muster sober, that she shouldn't have at all, drunk as she was. She saw the little man charge the bikers.

A spark of light leapt from the leader of the black-clad riders. It made a circuit of each biker, crackling from hand to hand until it returned to the leader. Then it arched out and the staff exploded. Not one of the riders had moved, but the staff hung in splinters from the little man's hand. A second spark made its circuit, darting from the leader to the little man. He stiffened, dancing on the spot as though he was being electrocuted, then he crumpled and fell to the ground in a limp heap. Jacky reached the closest biker at the same time.

As she reached out to grab the black-leather clad arm, the man turned. She looked for his face under his helmet, but there seemed to be nothing there. Only shadow, hidden by the smoked glass of a visor. She stumbled back as the rider twisted the accelerator control of his bike. The machine answered with a deep-throated growl and the bike pulled away.

One by one they moved out, the roar of their loud engines dwindling as they drew away. Jacky watched them return the way they'd come. She hugged herself, shaking. Then they were gone, around the corner, out of sight. The sound of the machines should have remained, but it too was cut off abruptly as the last machine disappeared from view.

Jacky took a step toward the little man. His head lay at an impossible angle, neck broken. Dead. She swallowed thickly, throat dry. She looked at the backs of the houses. There was still no sign that anyone in them had heard a thing. She hesitated, looking from the houses back to the broken body of the little man.

His cap had fallen when he'd collapsed, coming to rest not far from her feet. She picked it up. A man's dead, she thought. Those bikers … She remembered what she'd seen behind that one visor. Nothing. Shadow. But that had been because of the smoked glass. That had been just … her own fear. The shock of the moment.

She swallowed again, then started for the house where she'd seen the tall man watching. He'd be her witness that the bikers had been there. That she wasn't just imagining what had happened. But when she reached the backyard of that house, the building had an empty look to it. She looked to her right. There were the two marble birds. She looked back. This house was deserted, its yard overgrown with weeds. No one lived here. There hadn't been anyone watching ….

She shook her head. It was all starting to catch up with her now. The drinks. The shock of what she'd just witnessed. Her stupidity at just rushing in. It was all because of the weird head-trip she'd fallen into when Will had walked out … about being empty … and cutting her hair … She ran her fingers through the uneven thatch on her head. That much was real. Slowly she made her way back to where the little man's body lay.

There was nothing there. No dead little man. No tracks where the Harleys had torn up the sod. There was only the splintered staff and what looked like … She knelt down and reached out a hand. Ashes. A scatter of ashes. That was all that was left of the little man. Ashes and a splintered staff and … She brought up her other hand and looked down at the cap. And this.

Two

Jacky stayed home from work the next day. She was too hungover to go in, too embarrassed by her ragged hair, too exhausted after spending a night on her couch, dozing fitfully, waking from dreams filled with faceless bikers driving machines that were like wheeled dragons, who were looking for her ….

She spent the day going from her mirror to cleaning the apartment; from the mirror to stare at the strange red cap; from the mirror to force some toast and coffee into a queasy stomach; from the mirror to the toilet bowl where she lost the toast. She took a shower, but it didn't help. Finally, late in the day, she slept, not waking until midnight.

This time the toast stayed down, so she made herself some soup, ate it, and it stayed down as well. She stayed away from the mirror, hi

d the cap on the top shelf of her hall closet, and sat up watching Edward G. Robinson in The Last Gangster on the late show until she fell asleep again. But when she woke the next morning, she still couldn't face going to work.

It wasn't just her hair or the dissatisfaction that Will had awoken in her. She wasn't even afraid of what she'd seen – imagined? – two nights ago in the park. It was a combination of it all that left her realizing that things just weren't right with her world. She'd often seen herself as a round peg that everyone was trying to fit into a square hole. Her parents, her sister, Will, her co-workers … maybe even herself. Now she realized that she was more like a bit of scruffy flotsam, not moving against the flow as she'd liked to think privately, but just going wherever the flow pushed her. The path of least resistance. And it wasn't right.

She phoned in to work and put in for some time off that was owed to her. Her boss wasn't happy about giving it to her. Things were behind schedule – as always – but he gave it to her all the same. She had three weeks. Three weeks that she could use sitting in her apartment waiting for her hair to grow while she tried to decide what was important in her life – important to her, at least, if to no one else. Something that could be articulated so that she didn't have to have that helpless, hopeless feeling again that she'd had when Will tore into her last night.

She meant well, but her energy level was simply too low. It was all she could do to just sit on the sofa and alternate staring at mindless soap operas and game shows with gazing out the window. The phone rang a few times, but she ignored it. By the time the doorbell sounded around five, she felt so lethargic that she almost left it unanswered, as well, except that the doorbell was followed by a sharp rapping which, in turn, was followed by a familiar voice shouting through the door's wooden panels.

Widdershins

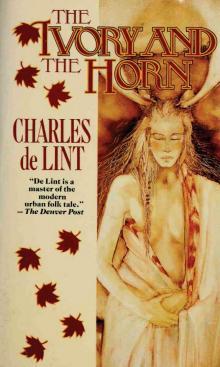

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

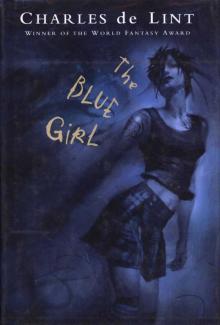

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn