- Home

- Charles de Lint

Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Read online

Moonlight

and Vines

By Charles de Lint from Tom Doherty Associates

ANGEL OF DARKNESS

DREAMS UNDERFOOT

THE FAIR IN EMAIN MACHA

FORESTS OF THE HEART

FROM A WHISPER TO A SCREAM

GREENMANTLE

I’LL BE WATCHING YOU

INTO THE GREEN

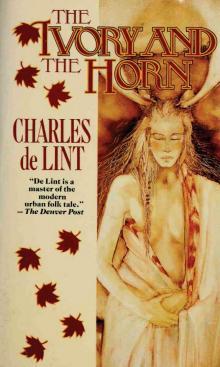

THE IVORY AND THE HORN

JACK OF KINROWAN

THE LITTLE COUNTRY

MEMORY AND DREAM

MOONHEART

MOONLIGHT AND VINES

MULENGRO

THE ONION GIRL

SOMEPLACE TO BE FLYING

SPIRITS IN THE WIRES

SPIRITWALK

SVAHA

TAPPING THE DREAM TREE

TRADER

WIDDERSHINS

THE WILD WOOD

YARROW

Moonlight

and Vines

A Newford Collection

Charles de Lint

The city, characters, and events to be found in these pages are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

MOONLIGHT AND VINES

Copyright © 1999 by Charles de Lint

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

Edited by Terri Windling

Designed by Nancy Resnick

Grateful acknowledgments are made to: Kiya Heartwood for the use of lines from her song “Robert’s Waltz” from the Wishing Chair album Singing with the Red Wolves (Terrakin Records). Copyright © 1996 by Kiya Heartwood, Outlaw Hill Publishing. Lyrics reprinted by permission. For more information about Kiya, her band Wishing Chair, or Terrakin Records, call 1-800-ROAD-DOG, or e-mail [email protected].

An Orb Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

www.tor.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

De Lint, Charles.

Moonlight and vines : a Newford collection / Charles de Lint.

p. cm.

“A Tom Doherty Associates book.”

ISBN 0-765-30917-3

EAN 978-0-765-30917-4

1. City and town life—North America—Fiction. 2. Newford (Imaginary

place)—Fiction. 3. Fantastic fiction, Canadian. I. Title.

PR9199.3.D357M67 1999

813'.54—dc21

98-44610

CIP

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4

“Sweetgrass & City Streets” is original to this collection.

“Saskia” first appeared in Space Opera, edited by Anne McCaffrey and Elizabeth Ann Scarborough; DAW Books, 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Charles de Lint.

“In This Soul of a Woman” first appeared in Love in Vein, edited by Poppy Z. Brite; HarperPrism, 1994. Copyright © 1994 by Charles de Lint.

“The Big Sky” first appeared in Heaven Sent, edited by Peter Crowther; DAW Books, 1995. Copyright © 1995 by Charles de Lint.

“Birds” first appeared in The Shimmering Door, edited by Katharine Kerr; Harper-Prism, 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Charles de Lint.

“Passing” was first published in Excalibur, edited by Richard Gilliam, Martin H. Greenberg and Edward E. Kramer; Warner Books, 1995. Copyright © 1995 by Charles de Lint.

“Held Safe by Moonlight and Vines” first appeared in Castle Perilous, edited by John DeChancie and Martin H. Greenberg; DAW Books, 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Charles de Lint.

“In the Pines” first appeared in Destination Unknown, edited by Peter Crowther; White Wolf Publishing, 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Charles de Lint.

“Shining Nowhere but in the Dark” first appeared in Realms of Fantasy, Vol. 3, No. 1, October, 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Charles de Lint.

“If I Close My Eyes Forever” is original to this collection.

“Heartfires” first appeared as a limited edition chapbook published by Triskell Press, 1994. Copyright © 1994 by Charles de Lint.

“The Invisibles” first appeared in David Copperfield’s Beyond Imagination, edited by David Copperfield and Janet Berliner; HarperPrism, 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Charles de Lint.

“Seven for a Secret” first appeared in Immortal Unicorn, edited by Peter S. Beagle and Janet Berliner, New York: HarperPrism, 1995. Copyright © 1995 by Charles de Lint.

“Crow Girls” first appeared as a limited edition chapbook published by Triskell Press, 1995. Copyright © 1995 by Charles de Lint.

“Wild Horses” first appeared in Tarot Fantastic, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Lawrence Schimel; DAW Books, 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Charles de Lint.

“In the Land of the Unforgiven” is original to this collection.

“My Life as a Bird” first appeared as a limited edition chapbook published by Triskell Press, 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Charles de Lint.

“China Doll” first appeared in The Crow: Shattered Lives and Broken Dreams, edited by James O’Barr and Edward E. Kramer; Del Rey, 1998. Copyright © 1998 by Charles de Lint.

“In the Quiet After Midnight” first appeared in Olympus, edited by Bruce D. Arthurs and Martin H. Greenberg; DAW Books, 1998. Copyright © 1998 by Charles de Lint.

“The Pennymen” first appeared in Black Cats and Broken Mirrors, edited by John Heifers and Martin H. Greenberg; DAW Books, 1998. Copyright © 1998 by Charles de Lint.

“Twa Corbies” first appeared in Twenty 3: A Miscellany, edited by Anna Hepworth, Simon Oxwell and Grant Watson; Infinite Monkeys/Western Australian Science Fiction Foundation, 1998. Copyright © 1998 by Charles de Lint.

“The Fields Beyond the Fields” first appeared as a limited edition chapbook published by Triskell Press, 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Charles de Lint.

for all those

who seek light

in the darkness

for all those

who shine light

into the darkness

Contents

Author’s Note

Sweetgrass & City Streets

Saskia

In This Soul of a Woman

The Big Sky

Birds

Passing

Held Safe by Moonlight and Vines

In the Pines

Shining Nowhere but in the Dark

If I Close My Eyes Forever

Heartfires

The Invisibles

Seven for a Secret

Crow Girls

Wild Horses

In the Land of the Unforgiven

My Life as a Bird

China Doll

In the Quiet After Midnight

The Pennymen

Twa Corbies

The Fields Beyond the Fields

Author’s Note

I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: No creative endeavor takes place in a vacuum. I’ve been very lucky in having incredibly supportive people in my life to help in the existence of these stories, be it in terms of the nuts and bolts of editing and the like, or on more elusive, inspirational levels. To name them all would be an impossible task, but I do want to mention at least a few:

First my wife MaryAnn, for fine-tuning the words, for asking the “What if?” behind the genesis of many of the fictional elements, and for making the writing process so much less lonely;

My longtime editor Terri Windling, and all the wonderful folks at Tor Books and at my Canadian distributor H. B. Fenn, but particularly Patrick Nielsen Hayden, Jenna Felice, Andy LeCount, Suzanne Halls-worth, and of course, Tom Doherty and Harold Fenn. Short-story collections aren’t exactly the bread and butter of the publ

ishing industry these days, but the interest and support they have shown for my previous collections, Dreams Underfoot and The Ivory and the Horn, are what helped to make them the successes that they are;

Friends such as Rodger Turner, Lisa Wilkins, Pat Caven, Andrew and Alice Vachss, Charles Saunders, Charles Vess, Karen Shaffer, Bruce McEwen, and Paul Brandon who are there to commiserate when I get whiny, and cheer me on when things are going well;

The individual editors who first commissioned these stories: Anne McCaffrey, Elizabeth Ann Scarborough, Poppy Z. Brite, Peter Crowther, Katharine Kerr, Richard Gilliam, Martin H. Greenberg, Edward E. Kramer, John DeChancie, Darrell Schweitzer, Neil Gaiman, Shawna McCarthy, Joe Lansdale, David Copperfield, Janet Berliner, Peter S. Beagle, Lawrence Schimel, Ed Gorman, James O’Barr, Bruce D. Arthurs, John Heifers, and Grant Watson;

And last, though certainly not least, my readers without whom these stories would only be soliloquies. From meeting many of you at various readings, signings, and other events, as well as the large amount of mail that arrives daily in my physical and virtual mailboxes, it’s readily obvious that I’m blessed with a loyal readership made up of those for whom taking the moment for a random act of kindness is as natural as breathing. Your continued support is greatly appreciated.

If you are on the Internet, come visit my home page. The URL (address) is http://www.cyberus.ca/~cdl.

—Charles de Lint

Ottawa, Spring 1998

Sweetgrass & City Streets

Bushes and briar,

thunder and fire.

In the ceremony

that is night,

the concrete forest

can be anywhere,

anywhen.

In the wail of a siren

rising up from the distance,

I hear a heartbeat,

a drumbeat, a dancebeat.

I hear my own

heart

fire

beat.

I hear chanting.

Eagle feather, crow’s caw

Coyote song, cat’s paw

Ya-ha-hey, hip hop rapping

Fiddle jig, drumbeat tapping

Once a

Once a

Once upon a time

I smell the sweet smoke

of smudge sticks,

of tobacco,

of sweetgrass on the corner

where cultures collide

and wisdoms meet.

And in that moment of grace,

where tales branch,

bud to leaf,

where moonlight

mingles with streetlight,

I see old spirits in new skins,

bearing beadwork,

carrying spare change and charms,

walking dreams,

walking large.

They whisper.

They whisper to each other

with the sound of talking drums,

finger pads brushing taut hides.

They whisper,

their voices carrying,

deliberately,

like distant thunder,

approaching.

Bushes and briar . . .

—Wendelessen

Saskia

The music in my heart I bore Long after it was heard no more.

—Wordsworth

1

I envy the music lovers hear.

I see them walking hand in hand, standing close to each other in a queue at a theater or subway station, heads touching while they sit on a park bench, and I ache to hear the song that plays between them: The stirring chords of romance’s first bloom, the stately airs that whisper between a couple long in love. You can see it in the way they look at each other, the shared glances, the touch of a hand on an elbow, the smile that can only be so sweet for the one you love. You can almost hear it, if you listen close. Almost, but not quite, because the music belongs to them and all you can have of it is a vague echo that rises up from the bittersweet murmur and shuffle of your own memories, ragged shadows stirring restlessly, called to mind by some forgotten incident, remembered only in the late night, the early morning. Or in the happiness of others.

My own happinesses have been few and short-lived, through no choice of my own. That lack of a lasting relationship is the only thing I share with my brother besides a childhood neither of us cares to dwell upon. We always seem to fall in love with women that circumstance steals from us, we chase after ghosts and spirits and are left holding only memories and dreams. It’s not that we want what we can’t have; it’s that we’ve held all we could want and then had to watch it slip away.

2

“The only thing exotic about Saskia,” Aaran tells me, “is her name.”

But there’s more going on behind those sea-blue eyes of hers than he can see. What no one seems to realize is that she’s always paying attention. She listens to you when you talk instead of waiting impatiently for her own turn to hold forth. She sees what’s going on at the periphery of things, the whispers and shadows and pale might-bes that most of us only come upon in dreams.

The first time I see her, I can’t look away from her.

The first time I see her, she won’t even look at me—probably because of the company I’m keeping. I stand at the far end of the club, wineglass in hand, no longer paying attention to the retro-Beat standing on the stage declaiming her verses in a voice that’s suddenly strident where earlier I thought it was bold. I’m not the only one Saskia distracts from the reading. She’s pretty and blonde with a figure that holds your gaze even when you’re trying to be polite and look away.

“Silicone,” Jenny informs me. “Even her lips. And besides, her forehead’s way too high. Or maybe it’s just that her head’s too long.”

Aaran nods in agreement.

Nobody seems to like her. Men look at her, but they keep their distance. Women arch their eyebrows cattily and smile behind their hands as they whisper to each other about her. No one engages her in conversation. They treat her so strangely that I find myself studying her even more closely, wondering what it is that I’m missing. She seems so normal. Attractive, yes, but then there are any number of attractive women in the room and none of them is being ostracized. If she’s had implants, she’s not the first to do so, and neither that nor the size of her forehead—which I don’t think is too large at all—seems to have any bearing on the reaction she seems to garner.

“She’s a poseur,” Aaran tries to explain. “A pretender.”

“Of what?” I ask.

“Of everything. Nothing about her is the way it seems. She’s supposed to be a poet. Supposed to be published, but have you ever heard of her?”

I shake my head, but what Aaran is saying doesn’t mean much in this context. There are any number of fine writers that I’ve never heard of and—judging from what I know of Aaran’s actual reading habits—the figure is even more dramatic for him.

“And then there’s the way she leads you on,” he goes on. “Leaning close like you’re the most important person in the world, but turning a cold shoulder the moment any sort of intimacy arises.”

So she turned you down? I want to ask, but I keep the question to myself, waiting for him to explain what he means.

“She’s just so full of herself,” Jenny says when Aaran falls silent. “The way she dresses, the way she looks down at everybody.”

Saskia is wearing faded jeans, black combat boots, a short white cotton blouse that leaves a few inches of her midriff bare, and a plaid vest. Her only jewelry is a small silver Celtic cross that hangs from a chain at the base of her throat. I look at my companions, both of them overdressed in comparison. Jenny in silk blouse and skirt, heels, a clutch purse, hair piled up at the back of her head in a loose bun. Nose ring, bracelets, two earrings per ear, a ring for almost every finger. Aaran in chinos and a dark sports jacket over a white shirt, goatee, hair short on top and sides, pulled into a tiny ponytail in back. One ear double-pierced like Jenny’s, the othe

r virgin. Pinky ring on each hand.

I didn’t come with either of them. Aaran’s the book editor for The Daily Journal and Jenny’s a feature writer for In the City, Newford’s little too-cool-to-not-be-hip weekly arts-and-entertainment paper. They have many of the personality traits they attribute to Saskia and the only reason I’m standing here with them is that it’s impolitic for a writer to make enemies with the press. I don’t seek out their company—frankly, I don’t care at all for their company—but I try to make nice when it’s unavoidable. It drives my brother Geordie crazy that I can do this. But maybe that’s why I can make a comfortable living, following my muse, while all too often he still has to busk on the streets to make his rent. It’s not that I don’t have convictions, or that I won’t defend them. I save my battles for things that have meaning instead of tilting at every mild irritation that comes my way. You can fritter away your whole life with those kinds of windmills.

“So no one likes her?” I ask my companions.

“Why should they?” Jenny replies. “I mean, beyond the obvious, and that’s got to wear thin once she opens her mouth.”

I don’t know what to reply to that, so I say, “I wonder why she comes around, then.”

“Why don’t you ask her yourself?” Aaran says with the same little smirk I see in too many of his reviews.

I’m thinking of doing just that, but when I look back across the club, she’s no longer there. So I return my attention to the woman on the stage. She’s onto a new poem now, one in which she dreams about a butcher’s shop and I’m not sure if she really does, or if it’s supposed to be a metaphor. Truth is, I’m not really listening to her anymore. Instead I’m thinking of Saskia and the way Aaran and Jenny have been sneering at her—physically and verbally—from the moment she walked in. I’m thinking that anyone who can call up such animosity from these two has got to have something going for her.

The poet on stage dreams of cleavers and government-approved steaks. That night I dream of Saskia and when I wake up in the morning the events of last night’s reading in the club and my dream are all mixed up together. It takes the first coffee of the morning for me to sort them all out.

Widdershins

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn