- Home

- Charles de Lint

The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Read online

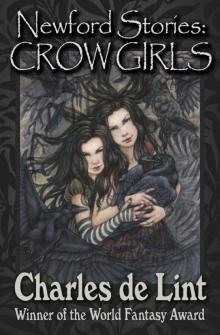

Newford Stories: Crow Girls

by

Charles de Lint

Copyright © 2015 by Charles de Lint

Smashwords Edition, License Notes:

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

for MaryAnn

CONTENTS

Introduction by Joanne Harris

Crow Girls

Twa Corbies

The Buffalo Man

A Crow Girls’ Christmas

Make a Joyful Noise

Afterword

Copyrights & Acknowledgements

About the Author

Someplace to Be Flying excerpt

Introduction

by

Joanne Harris

I first came across the work of Charles de Lint in the early nineties. I’d just given birth, both to my daughter and to my second book, Sleep, Pale Sister, a dark little tale about ghosts and the Victorian art community. I was already writing another book, whilst working full-time as a teacher, having taken only two weeks’ maternity leave. It wasn’t a wonderful time for me. I had terrible headaches. I barely slept. I felt I was living a different life to the one I was meant to live; I used to look at the evening sky and dream of simply flying away.

One day I pulled out a book at random from a shelf in the city library. It was called Memory and Dream. As I leafed through the pages, two glossy black feathers fell out. That was my first introduction to Charles’ curiously evocative, uniquely quirky, urban and yet wistful depiction of otherworldly spirits in human form, living in plain sight in those places where dream and reality intersect. I read the book, and found that it put into words thoughts I’d had about my life, but hadn’t known how to articulate. It was a breath of unpolluted air; a whisper of everyday magic.

Since then I have sought out Charles’ books wherever I could find them—although they are not always easy to find in the UK—and have read them with admiration and joy. No other writer does what he does in depicting the process of making art—be that painting, sculpture, writing or music. He writes with a passion and authority that only experience can give, and his words have hidden cadences that echo the rhythms of the music he loves, and conjure the secret landscapes between the world of what we know and the worlds we dare to dream.

His books are filled with characters we feel we must have met before; and maybe we have (those two feathers were certainly put there by someone); but in any case, the crow girls and their kind, once seen, are impossible to forget. Wild, but curiously childlike; wise and yet playful; existing outside the confines of conventional morality, and yet bringing hope and clarity to everyone whose lives they touch. Like Odin’s ravens, Hugin and Munin, they seem to be an expression of our collective mind and spirit, of freedoms lost and instincts suppressed; of a simplicity of purpose and connection with the natural world that modern living has taken from us, and that we now find only in dreams, in art, in the wilderness and just occasionally, in stories like these.

This collection of Newford stories offers a glimpse behind the scenes of the everyday world into a modern dreamtime, in which the spirits of the First People cast their shadows across our lives, leaving in their wake a sense of something lost and something found—a breath of other places; a possibility of reconciliation between Man and the natural world.

Coleridge imagined a scene in which a sleeper, dreaming of Heaven, picked a flower there, only to find it in his hand as he awoke. These stories—ephemeral, bittersweet—are a reminder that what has been lost may also be re-imagined; a token of the bond between mind and spirit; body and soul; a flower picked in Paradise—

Or, just maybe, a feather.

Crow Girls

I remember what somebody said about nostalgia. He said, “It’s okay to look back, as long as you don’t stare.”

—Tom Paxton, from an interview with Ken Rockburn

People have a funny way of remembering where they’ve been, who they were. Facts fall by the wayside. Depending on their temperament, they either remember a golden time when all was better than well, better than it can be again, better than it ever really was: a first love, the endless expanse of a summer vacation, youthful vigor, the sheer novelty of being alive that gets lost when the world starts wearing you down. Or they focus in on the bad, blow little incidents all out of proportion, hold grudges for years, or maybe they really did have some unlucky times, but now they’re reliving them forever in their heads instead of moving on.

But the brain plays tricks on us all, doesn’t it? We go by what it tells us, have to, I suppose, because what else do we have to use as touchstones? Trouble is, we don’t ask for confirmation on what the brain tells us. Things don’t have to be real, we just have to believe they’re real, which pretty much explains politics and religion as much as it does what goes on inside our heads.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not pointing any fingers here. My people aren’t guiltless either. The only difference is our memories go back a lot further than yours do.

* * *

“I don’t get computers,” Heather said.

Jilly laughed. “What’s not to get?”

They were having cappuccinos in the Cyberbean Café, sitting at the long counter with computer terminals spaced along its length the way those little individual jukeboxes used to be in highway diners. Jilly looked as though she’d been using the tips of her dark ringlets as paintbrushes, then cleaned them on the thighs of her jeans—in other words, she’d come straight from the studio without changing first. But however haphazardly messy she might allow herself or her studio to get, Heather knew she’d either cleaned her brushes, or left them soaking in turps before coming down to the café. Jilly might seem terminally easygoing, but some things she didn’t blow off. No matter how the work was going—good, bad or indifferent—she treated her tools with respect.

As usual, Jilly’s casual scruffiness made Heather feel overdressed. She was only wearing cotton pants and a blouse, nothing fancy. But she always felt a little like that around Jilly, ever since she’d first taken a class from her at the Newford School of Art a couple of winters ago. No matter how hard she tried, she hadn’t been able to shake the feeling that she looked so typical: the suburban working mother, the happy wife. The differences since she and Jilly had first met weren’t great. Her blond hair had been long then, while now it was cropped short. She was wearing glasses now instead of her contacts.

And two years ago she hadn’t been carrying an empty wasteland around inside her chest.

“Besides,” Jilly added. “You use a computer at work, don’t you?”

“Sure, but that’s work,” Heather said. “Not games and computer screen romances and stumbling around the Internet, looking for information you’re never going to find a use for outside of Trivial Pursuit.”

“I think it’s bringing back a sense of community,” Jilly said.

“Oh, right.”

“No, think about it. All these people who might have been just vegging out in front of a TV are chatting with each other in cyberspace instead—hanging out, so to speak, with kindred spirits that they might never have otherwise met.”

Heather sighed. “But it’s not real human contact.”

“No. But at least it’s contact.”

“I suppose.”

Jilly regarded her over the brim of her glass coffee mug. It was a mild gaze, not in the least pr

obing, but Heather couldn’t help but feel as though Jilly were seeing right inside her head, all the way down to where desert winds blew through the empty space where her heart had been.

“So what’s the real issue?” Jilly asked.

Heather shrugged. “There’s no issue.” She took a sip of her own coffee, then tried on a smile. “I’m thinking of moving downtown.”

“Really?”

“Well, you know. I already work here. There’s a good school for the kids. It just seems to make sense.”

“How does Peter feel about it?”

Heather hesitated for a long moment, then sighed again. “Peter’s not really got anything to say about it.”

“Oh, no. You guys always seemed so…” Jilly’s voice trailed off. “Well, I guess you weren’t really happy, were you?”

“I don’t know what we were anymore. I just know we’re not together. There wasn’t a big blowup or anything. He wasn’t cheating on me and I certainly wasn’t cheating on him. We’re just…not together.”

“It must be so weird.”

Heather nodded. “Very weird. It’s a real shock, suddenly discovering after all these years that we really don’t have much in common at all.”

Jilly’s eyes were warm with sympathy. “How are you holding up?”

“Okay, I suppose. But it’s so confusing. I don’t know what to think, who I am, what I thought I was doing with the last twenty years of my life. I mean, I don’t regret the girls—I’d have had more children if we could have had them—but everything else…”

She didn’t know how to begin to explain.

“I married Peter when I was eighteen and I’m forty-one now. I’ve been a part of a couple for longer than I’ve been anything else, but except for the girls, I don’t know what any of it meant anymore. I don’t know who I am. I thought we’d be together forever, that we’d grow old together, you know? But now it’s just me. Casey’s fifteen and Janice is twelve. I’ve got another few years of being a mother, but after that, who am I? What am I going to do with myself?”

“You’re still young,” Jilly said. “And you look gorgeous.”

“Right.”

“Okay. A little pale today, but still.”

Heather shook her head. “I don’t know why I’m telling you this. I haven’t told anybody.”

“Not even your mom or your sister?”

“Nobody. It’s…”

She could feel tears welling up, the vision blurring, but she made herself take a deep breath. It seemed to help. Not a lot, but some. Enough to carry on. How to explain why she wanted to keep it a secret? It wasn’t as though it was something she could keep hidden forever.

“I think I feel like a failure,” she said.

Her voice was so soft she almost couldn’t hear herself, but Jilly reached over and took her hand.

“You’re not a failure. Things didn’t work out, but that doesn’t mean it was your fault. It takes two people to make or break a relationship.”

“I suppose. But to have put in all those years…”

Jilly smiled. “If nothing else, you’ve got two beautiful daughters to show for them.”

Heather nodded. The girls did a lot to keep the emptiness at bay, but once they were in bed asleep and she was by herself, alone in the dark, sitting on the couch by the picture window, staring down the street at all those other houses just like her own, that desolate place inside her seemed to go on forever.

She took another sip of her coffee and looked past Jilly to where two young women were sitting at a corner table, heads bent together, whispering. It was hard to place their ages—anywhere from late teens to early twenties, sisters, perhaps, with their small builds and similar dark looks, their black clothing and short blue-black hair. For no reason she could explain, simply seeing them made her feel a little better.

“Remember what it was like to be so young?” she said.

Jilly turned, following her gaze, then looked back at Heather.

“You never think about stuff like this at that age,” Heather went on.

“I don’t know,” Jilly said. “Maybe not. But you have a thousand other anxieties that probably feel way more catastrophic.”

“You think?”

Jilly nodded. “I know. We all like to remember it as a perfect time, but most of us were such bundles of messed-up hormones and nerves I’m surprised we ever managed to reach twenty.”

“I suppose. But still, looking at those girls…”

Jilly turned again, leaning her head on her arm. “I know what you mean. They’re like a piece of summer on a cold winter’s morning.”

It was a perfect analogy, Heather thought, especially considering the winter they’d been having. Not even the middle of December and the snowbanks were already higher than her chest, the temperature a seriously cold minus fifteen.

“I have to remember their faces,” Jilly went on. “For when I get back to the studio. The way they’re leaning so close to each other—like confidantes, sisters in their hearts, if not by blood. And look at the fine bones in their features…how dark their eyes are.”

Heather nodded. “It’d make a great picture.”

It would, but the thought of it depressed her. She found herself yearning desperately in that one moment to have had an entirely different life, it almost didn’t matter what. Perhaps one that had no responsibility but to draw great art from the world around her, the way Jilly did. If she hadn’t had to support Peter while he was going through law school, maybe she would have stuck with her art….

Jilly swiveled in her chair, the sparkle in her eyes deepening into concern once more.

“Anything you need, anytime,” she said. “Don’t be afraid to call me.”

Heather tried another smile. “We could chat on the Internet.”

“I think I agree with what you said earlier: I like this better.”

“Me too,” Heather said. Looking out the window, she added, “It’s snowing again.”

* * *

Maida and Zia are forever friends. Crow girls with spiky blue-black hair and eyes so dark it’s easy to lose your way in them. A little raggedy and never quiet, you can’t miss this pair: small and wild and easy in their skins, living on Zen time. Sometimes they forget they’re crows, left their feathers behind in the long ago, and sometimes they forget they’re girls. But they never forget that they’re friends.

People stop and stare at them wherever they go, borrowing a taste of them, drawn by they don’t know what, they just have to look, try to get close, but keeping their distance, too, because there’s something scary/craving about seeing animal spirits so pure walking around on a city street. It’s a shock, like plunging into cold water at dawn, waking up from the comfortable familiarity of warm dreams to find, if only for a moment, that everything’s changed. And then, just before the way you know the world to be comes rolling back in on you, maybe you hear giddy laughter, or the slow flap of crows’ wings. Maybe you see a couple of dark-haired girls sitting together in the corner of a café, heads bent together, pretending you can’t see them, or could be they’re perched on a tree branch, looking down at you looking up, working hard at putting on serious faces but they can’t stop smiling.

It’s like that rhyme, “two for mirth.” They can’t stop smiling and neither can you. But you’ve got to watch out for crow girls. Sometimes they wake a yearning you’ll be hard-pressed to put back to sleep. Sometimes only a glimpse of them can start up a familiar ache deep in your chest, an ache you can’t name, but you’ve felt it before, early mornings, lying alone in your bed, trying to hold on to the fading tatters of a perfect dream. Sometimes they blow bright the coals of a longing that can’t ever be eased.

* * *

Heather couldn’t stop thinking of the two girls she’d seen in the café earlier in the evening. It was as though they’d lodged pieces of themselves inside her, feathery slivers winging dreamily across the wasteland. Long after she’d played a board game with Janice, th

en watched the end of a Barbara Walters special with Casey, she found herself sitting up by the big picture window in the living room when she should be in bed herself. She regarded the street through a veil of falling snow, but this time she wasn’t looking at the houses, so alike except for the varying heights of their snowbanks, they might as well all be the same one. Instead, she was looking for two small women with spiky black hair, dark shapes against the white snow.

There was no question but that they knew exactly who they were, she thought when she realized what she was doing. Maybe they could tell her who she was. Maybe they could come up with an exotic past for her so that she could reinvent herself, be someone like them, free, sure of herself. Maybe they could at least tell her where she was going.

But there were no thin, dark-haired girls out on the snowy street, and why should there be? It was too cold. Snow was falling thick with another severe winter storm warning in effect tonight. Those girls were safe at home. She knew that. But she kept looking for them all the same because in her chest she could feel the beat of dark wings—not the sudden panic that came out of nowhere when once again the truth of her situation reared without warning in her mind, but a strange, alien feeling. A sense that some otherness was calling to her.

The voice of that otherness scared her almost more than the grey landscape lodged in her chest.

She felt she needed a safety net to be able to let herself go and not have to worry about where she fell. Someplace where she didn’t have to think, be responsible, to do anything. Not forever. Just for a time.

She knew Jilly was right about nostalgia. The memories she carried forward weren’t necessarily the way things had really happened. But she yearned, if only for a moment, to be able to relive some of those simpler times, those years in high school before she’d met Peter, before they were married, before her emotions got so complicated.

Widdershins

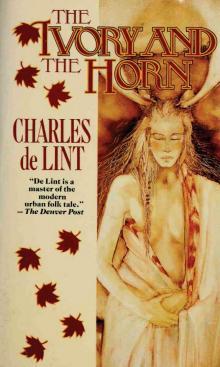

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn