- Home

- Charles de Lint

Into the Green

Into the Green Read online

Into the Green

Charles de Lint

By Charles de Lint

Dreams Underfoot

The Fair at Emain Macha

Into the Green

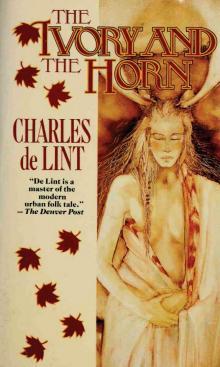

The Ivory and the Horn

The Little Country

Memory and Dream

Moonheart

Spiritwalk

Svaha

Copyright © 1993 by Charles de Lint

Into the Green

A Peanut Press Book

Published by Peanut Press

www.peanutpress.com

ISBN: 0-7408-0346-8

First Peanut Press Edition

for the Oxford boys & girls (official and honorary) for songs, support and great good cheer

With special thanks to MZB, who first sent me looking for these stories, and to Diana for her own.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The early portion of this novel appeared, in much altered form, as short stories in Marion Zimmer Bradley's SWORD AND SORCERESS anthology series from DAW Books.

To those interested in this kind of thing, "Angharad" is pronounced "Ann-ar-ad," "ar" pronounced as it is in "car," "ad," as in "lad".

Heather am I and I restore luck

I am the queen of every hive

Reddening the mountains in midsummer

Stag and stone revere my harping

— Wendelessen,

from "Four Seasons,

and the First Day of the Year"

1

Angharad's people met the witches the night they camped by Tiercaern, where the heather-backed Carawyn Hills flow down to the sea.

There were two of them— an old winter of a man, with salt-white hair and skin as brown and wrinkled as a tinker's hand, and a boy Angharad's age, fifteen summers if he was a day, lean and whip-thin, with hair as black as a sloe. They had the flicker of blue-gold in the depths of their eyes— eyes that were both old and young, of all ages and of none.

The tinkers had brought their canvas-topped wagons around in a circle and were preparing supper when the pair approached the edge of the camp. They hailed the tinkers above the sudden warning chorus of the camp dogs, and Angharad's father, Herend'n, went out to meet them, for he was the leader of the company.

"Is there iron on you?" Herend'n called, by which he meant, were they carrying weapons.

The old man shook his head and lifted his staff. It was a white wood, that staff; cut from a rowan: witch-wood.

"Not unless you count this," he said. "My name's Woodfrost and this is Garrow, my grandson. We are travelers— like yourselves."

Angharad, peering at the strangers from behind her father's back, saw the blue-gold light in their eyes and shook her head. They weren't like her people. They weren't at all like any tinkers she knew.

Her father regarded the strangers steadily for a long heartbeat, then stepped aside and ushered them into the wagon circle.

"Be welcome," he said.

When they were by his fire, he offered them the guest-cup with his own hands. Woodfrost took the tea and sipped. Seeing them up close, Angharad wondered why the housey-folk feared witches so. This pair was as bedraggled as a couple of cats caught out in a storm and seemed no more frightening to her than beggars in a market town square. They were skinny and poor, with ragged travel-stained cloaks and unkempt hair. But then the old man's gaze touched hers and suddenly Angharad was afraid.

There was a distance in those witch-eyes, like a night sky rich with stars, or like a hawk floating high on the wind, watching, waiting to drop on its prey. They read something in her, pierced the scurry of her thoughts and the motley mix of what she was, to find something lacking. She couldn't look away, she was trapped like a riddle on a raven's tongue, until he finally dropped his gaze. Shivering, Angharad moved closer to her father.

"I thank you for your kindness," Woodfrost said as he handed the guest-cup back to Herend'n. "The road can be hard for folk such as we— especially when there is no home waiting for us at road's end."

Again his gaze touched Angharad.

"Is this your daughter?" he added.

Herend'n nodded proudly and gave the old man her name. He was a widower and with the death of Angharad's mother many years ago much of his joy in life had died. But if he loved anything in this world, it was his colt-thin daughter with her brown eyes that were so big and the bird's-nest tangle of her red hair.

"She has the sight," Woodfrost said.

"I know," Herend'n replied. "Her mother had it too— Ballan rest her soul."

Bewildered, Angharad looked from her father to the stranger. This was the first she'd heard of it.

"But Da," she said, pulling at his sleeve.

He turned at the tug to look at her. Something passed across his features the way the grass in a field trembles like a wave when the wind touches it. It was there one moment, gone the next— a sadness, a touch of pride, a momentary fear.

"But, Da," she repeated.

"Don't be afraid," he said. "It's but a gift— like Kinny's skill with a fiddle, or the way Sheera can set a snare and talk to her ferrets."

"I'm not a witch!"

"It isn't such a terrible thing," Woodfrost said gently.

Angharad refused to meet his gaze. Instead, she looked at the boy. He smiled back shyly. Quickly Angharad looked away.

"I'm not," she said again, but now she wasn't so sure.

She wasn't exactly sure what the sight was, but she could remember a time when she'd seen more in the world than those around her. But she'd been so young then and it all went away when she grew up.

Or she had made it go away...

—

As though the coming of the witches was a catalyst, Angharad found that once again she could see what was hidden from others. Again she was aware of movement abroad in the world that went unseen and unheard by both tinkers and the housey-folk who lived in the towns or worked the farms, and to see it, to hear it, was not such a terrible thing.

Woodfrost and Garrow traveled with the company that whole summer long and will she, nill she, Angharad learned to use her gift. She retained her fear of Woodfrost— because there was always that shadow, that darkness, that secrecy in his eyes— but she made friends with Garrow. He was still shy with the other tinkers, but he opened up to her. His secrets, when they unfolded, were of a far and distant sort from what she supposed his grandsire's to be.

Garrow taught her the language of the trees and the beasts, from the murmur of a drowsy oak to the quick chatter of squirrel and finch, and the sly tongue of the fox. Magpies became her confidants, and badgers, and the wind. But at the same time she found herself becoming tongue-tied around Garrow. If he paid particular attention to her, or caught one of her long dreamy glances, a flush would rise from the nape of her neck and her heart began to beat quick and fast like that of a captured wren.

—

On a night between the last days of the Summerlord Hafarl's rule and the first cold days of autumn, on a night when the housey-folk left their farms and towns to build great bonfires on the hilltops where they sang and danced to music that made the priests of the One God Dath frown, she and Garrow made a mystery of their own. They made love as gently fierce as the stag and moon in the spring and, afterwards, lay dreamy and content in each other's arms while the stars completed their nightly wheel and spin in the skies high above them.

When Garrow finally slept, tears touched Angharad's cheeks, but it wasn't for sorrow that she wept. She was so full of emotion and magic that there was simply no other release for what she felt swelling inside her.

—

The tinker company wintered in Mullion that year, on a farm that belonged to Green George Snell, who once traveled the roads with Angharad's people. There they prepared

for the next year's traveling. Wagons were repaired, as were harnesses and riggings. Goods were made to be sold at the market towns and the horses were readied for the fairs.

When the first breath of spring was in the air, the company took to the road once more. Angharad and Garrow still rode in Herend'n's wagon, though they had jumped the broom at midwinter. Newly married, they were still too poor to afford their own wagon.

The road took them up into Umbria and Kellmidden that summer, where the company looked to meet with the caravans of other travelers and to grow rich— or at least as rich as any tinker could get, which was not a great deal by the standards of the housey-folk. They looked forward to a summer of traveling and the road, of gossiping and trading, of renewing old acquaintances and making new friends.

Instead, they found the plague waiting for them.

2

The sight of that first devastated town cut into Angharad like a sharp sliver thrust deep into her heart. All she could do was stare at the corpse where it lay in the town square, black and swollen. Around her, the tinkers' shocked gazes found more bodies, and then more still— in alleyways, in doorways. The entire population of the town was an ungainly sprawl of corpses, black from the plague, lying wherever they'd fallen and taken their last breath.

Too late, Herend'n realized their plight.

The town had been oddly silent, but the tinkers hadn't remarked on that as their wagons rolled out of the moors and made their way down the long gentle slope to where the buildings clustered by the river ford. Not one of them had noticed the lack of smoke rising from the chimneys of the buildings, the empty streets, the disquiet of the camp dogs, the empty pastures about the town.

It wasn't until they reached the town square, where that first corpse lay blocking their way, that they realized something was dangerously amiss, and by then it was too late.

Herend'n allowed no one to alight. He immediately turned the wagons and prayed to the Lord of Broom and Heather to protect them; but two nights later the first of the company took sick all the same. In retrospect, Herend'n realized that one of the camp dogs must have spread the sickness. When Angharad and the witches saw the plague spreading under the skin of Marenda's son Fearnol, Herend'n turned the wagons into their circle and they set up camp.

But it was far too late.

By nightfall, half the company was stricken. In two weeks' time, for all the medicines that Angharad and the witches and the rootwives of the tinkers gathered and prepared and fed to the sick, the greater part of the company was dead.

Nine wagons were in that circle and sixty-two tinkers had traveled in them. On the morning that the last of the dead were buried, only one wagon left the camp and only three of the company rode in it. They were thin and gaunt as half-starved ravens: Jend'n the Tall, Sheera's daughter Benraida, and Crowen the Kettle-maker.

There was a fourth survivor— Angharad. But she remained behind with her dead. Her father. Her husband. Her kin. Her friends.

She lived in her father's wagon and tended their graves the whole summer long. She cursed the sight that had made her see the black sickness speed and swell inside the bodies of the stricken, killing them cell by cell, while she stood helplessly by.

Garrow. Her father...

She cursed what gods she knew of, from Ballan, the Lord of Broom and Heather, to Dath, the cold One God, and Hafarl's daughter to whom she had always felt the closest: gentle Tarasen, who kept safe the beasts of the wood and the birds of the air. Even she had failed Angharad in her time of need.

Angharad stayed there until the summer drew to an end, and then she remembered a tale once heard around the fires of a tinker camp, of marshes and Jacky Lantern's kowrie kin, of how the dead could be called back in such a place, if one's need were great enough, if one had the gift...

She took to the road the next morning with a small pack of provisions slung over one shoulder and Woodfrost's white staff in her hand. She went through a land empty and deserted, through villages and towns where the dead lay unburied, past farms that were silent and forsaken as broken dreams. She traveled through the wild north highlands of Umbria, and when she crossed Kellmidden's borders it was to come to a land that the plague had never grasped in its diseased claws.

And still she did not understand why she had been spared when so many had died.

Hafarl's grip was loosing on the land as the autumn grew crisp across the dales and hills of Kellmidden's lowlands; the constellations that wheeled above her by night were those of Lithun, the Winterlord. She stopped to sup in a last inn, ignoring the warnings of the well-meaning housey-folk that stayed warm by the fire when she went out into the night once more.

Don't go by night, they said. But she did.

Don't stray from the road, they said. But she did.

Don't follow the fire; don't listen to its music. But she did.

They meant well, she knew, but they didn't understand. She sought the blue-gold fire and the fey music of Jacky Lantern's elusive kin.

It was all she had left.

She went empty-handed now, her provision bag depleted and the rowan staff no longer needed, for she knew she was approaching the end of her journey. As she had eaten her supper in the inn, she'd heard the sweet fey music... calling to her, whispering, drawing her on, unattainable as fool's fire, but calling to her all the same. When she left the road and entered the dark forests, Garrow's features swam in her mind's eye, a familiar smile playing on his lips, keyed to the fey, unearthly music that came to her from the depths of the forest.

It was then that she knew her journey was done.

3

As she left the road, the forest closed in around her, dark and rich with scent and sound. The wind spoke in the uppermost branches with a murmur that almost, but not quite, buried the sound of a distant harp music coming to her from deeper in the wood. Her witch-sight pierced the gloom, searching for the first trace of a willo'-the-wisp's lantern, bobbing in amongst the trees.

But there was nothing to see. There was only the music.

She hurried on, going more and more quickly. Tears ran down her cheeks as all her losses rose to follow her ever more deeply into the forest. Finally she stumbled, foot snagged by a root. She only just caught herself from falling by catching hold of a low-hanging branch. She leaned against the fat bole of the tree to which it was attached. The bark was rough against her skin and pulled at her hair as she moved her head slowly away from it.

As though echoing her pain, the distant harping faltered and grew still.

She lifted her head, afraid of the sudden silence. Then faintly, faintly, the music started up once more and she went on, trying to keep the memories buried, but they rose, constant as air bubbles in a sulfur spring, the pain spreading through her as pervasively as those noxious fumes fouled the air about themselves.

The land sloped steadily downward in the direction she was traveling. The forest of pine, birch and fir gave way to gnarly cedars and stands of willow. Underfoot, the ground softened and her passage was marked by the soft sucking noise of her feet lifting from the marshy footing.

A sliver of a horned moon was lowering in the west: Anann's last quarter, a moon of omens.

The muck rose to her ankles and the long days of her journeying and sorrow finally took their toll. Weary beyond belief, she collapsed on a small hillock that rose out of the marsh. The fey harping was no louder than it had ever been, but somehow it seemed closer now. On arms trembling from fatigue, she lifted her upper body from the ground and rolled over to see the makers of that music standing all around her.

They were tall ghostly beings, thin as reeds and glowing with their own pale inner light. Their hair hung thin and feather soft about their long and narrow faces. The men carried lanterns filled with flickering light— fool's fire; the women played harps that were as slender as willow boughs, with strings like spun moonlight. Their eyes gleamed blue-gold in the darkness.

Strayed, the harping sang to her. A ghostly refrain. T

oo far... too far...

She looked amongst their ranks for another slender form— a familiar form, with black hair and no harping skill— but saw only the ghostly harpers and lantern-bearers.

"Garrow?" she called, searching their faces.

The harping fluttered like a chorus of bird calls, then grew still. Angharad's heartbeat stilled with it. She held her breath as one of the pale glowing shapes moved forward.

"You!" she cried.

The anger in her voice was plain as she recognized the man's features. Her pulse drummed suddenly, loud in her ears, driven by a mingling of that anger and fear.

Woodfrost nodded wearily. "You are still so stubborn," he said.

She glared at him. "What have you done with Garrow?" she demanded. "I didn't come for you, old man."

"As a child you could see," Woodfrost went on as though he hadn't heard her, "but you realized soon enough that others couldn't and, rather than be different, you ignored the gift until you became as blind as they were. Ignored it so that, in time, all memory of it was gone."

"It was a curse, not a gift," Angharad said. "How can you call it a gift when it allows you to see those you love die, while you must stand helplessly by?"

"So many years you wasted," Woodfrost continued, still ignoring her. "So stubborn. And then we came to your camp, my grandson and I. Still you protested, until Garrow drew the veil from your eyes and taught you your gift once more— taught you what you had once known, but chose to forget. Was your gift so evil then?"

Angharad wanted to stand, but her body was too tired to obey her. She managed to sit up and hug her knees.

"Garrow was alive then," she said.

Woodfrost nodded. "So he was. And then he died. Death is a tragedy— no mistake of that, Angharad— but only for the living. We who have died go on to... other things, as the living must go on with the responsibility of being alive. But not you. Oh, no. You are too stubborn for that. If those you love are dead, then you will go about as one dead yourself. It is a fine thing to revere those who have passed on— but only within reason, Angharad. Graves may be tended and memories called up, but the business of living must go on."

Widdershins

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn