- Home

- Charles de Lint

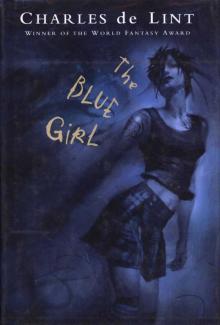

The Blue Girl Page 10

The Blue Girl Read online

Page 10

I felt horrible about holding back when we exchanged confidences, but all I could seem to do was tell her the things I knew she’d like: My first kiss. Little Bob’s stories. Emmy Jean’s advice. Life on the commune.

Or problems we shared, like the bullying we’d both had to endure at school.

I didn’t want her to think the life I’d had back then was cool—the way I had at the time. And I couldn’t talk about it like it wasn’t, even though I no longer believed it myself. Does that make any sense?

“Hey, Adrian,” I called out softly as we walked down the dark hallway. “You’ve got company.”

There was no reply except for the soft echo of my voice going down the empty hall.

“It’s weird being in here when there’s no one else around,” Maxine said.

I nodded, remembering that first Sunday afternoon that I’d snuck in. Now it was old hat, and wasn’t that an odd expression? I’d have to look it up in my Brewer’s when I got home.

“Especially at night,” Maxine went on. I could hear the nervousness in her voice and wondered if we’d have to leave, but then she added in a lighter tone, “Hey, here’s my old locker. I wonder if there’s a way for us to get lockers beside each other this year.”

I laughed. “Your mom could probably make it happen.”

“My mom?”

“Remember I told you how she got Ms. Kluge to cough up my old school records?”

Maxine nodded. “Yeah, Mom doesn’t take the word no well. But I don’t think I’ll ask her all the same.” She looked down the shadowy hall. “So where’s the ghost?”

“I don’t know. Except for that first time when I had to wander around for an hour or so, he usually shows up pretty quickly.”

“Maybe he went out—he can go out, right?”

“Yeah, but he doesn’t like to.”

“Why not?”

I shrugged. “Something about angels and the darkness.”

“The darkness?” Maxine repeated. “That doesn’t sound good.”

“Relax. Whatever it is, it’s only dangerous to spirits like Adrian.”

“And the angels?”

“I don’t know what they are either. That’s just what he calls them.”

We were well into the school by now, and there was still no sign of Adrian. I found myself wondering if I should have taken him up on one of his offers to show me those elf bolts he kept talking about. Maybe he was in one of them right now, fast asleep or something. That’s if ghosts slept. I’d have to ask him about that the next time I saw him. But tonight was a bust.

I was just about to say as much to Maxine when we both heard a noise down the hall from where we were walking. We stopped, listening hard, and then heard the echoing sound of footsteps. They were definitely approaching us.

“So ...” Maxine said in a whisper, the nervousness back in her voice. “If Adrian’s a ghost, and ghosts don’t have bodies, then who—”

Before she could finish, Mr. Sanderson, the janitor, stepped out of a side hall.

“Hey, you girls!” he cried. “What do you think you’re doing in here?”

“Oh, crap,” I said.

I grabbed Maxine’s hand and started to run in the opposite direction.

“You get your asses back here!” Mr. Sanderson called after us.

Oh right, as if.

The empty hall was suddenly filled with the sound of our running and the janitor’s yelling. I doubt he’d have caught us, but before we got a chance to find out, I heard him stumble and fall down.

I shot a glance over my shoulder, then skidded to a halt, hauling Maxine to a stop beside me. Looking back, we saw the janitor backed against some lockers, arms scrabbling in the air.

“Get off me, get off me!” he cried.

“What’s the matter with him?” Maxine asked.

“D.T.’s,” I said. “Come on. Let’s get out of here.”

We burst out the side door and kept running until we were by the big cedar hedge that separated the school from the sunken parking lot of the apartment building next door. It was a place kids came to smoke dope during recess—a perfect spot because, once you got into it, you could see out, but no one could see you in the shadows.

I pushed in through the branches, Maxine on my heels, only stopping when I came up to the cement wall of the parking lot. We stood there, holding onto the hedge and each other as we caught our breaths. Finally, I was able to peer out into the schoolyard without feeling like my gasps for air would be heard a block away. I was just in time to see Mr. Sanderson bang open the door and stand there swaying as he glared into the schoolyard.

Maxine and I held our breaths.

The janitor muttered something I couldn’t quite make out as he finally turned away and let the door clang shut behind him.

“That was close,” I said.

“Do you always have to—”

“Run from a drunk janitor?” I finished. “No, but I do try to avoid him. He’s usually in the basement, either drinking, or sleeping off a drunk on this little cot he’s got down there.”

“We’re lucky he didn’t call the cops.”

“He still might, so we should get out of here.”

Which was a great idea except that as soon as we pushed our way out of the hedge, a familiar voice spoke out of the darkness.

“Imogene. What are you doing here?”

I turned and there he was: Adrian in all his ghostly glory, which was basically Adrian standing there all tall and gawky with a puzzled look on his face. I heard Maxine’s sharp intake of breath and put a hand on her arm.

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s just Adrian.”

“I ... I figured as much. It’s just ... he’s so real ...”

“But he won’t bite, right, Adrian?”

He shook his head. “Nope. I’m a ghost, not one of the undead.”

“There are undead?” Maxine asked, moving closer to me so that our hips bumped. “Like, vampires?”

“There’s anything you can imagine and then some,” he told her. “They just live at the edges of the world that you know, so you don’t usually see them.”

“Right,” I said. “Amp up the spooky factor.”

He turned back to me. “I’m only telling the truth. So what are you doing out here, hiding in a hedge?”

“I brought Maxine around so that you could meet her, but you weren’t at the school.”

“I was out, just, you know, walking ...”

“Whatever. We got caught by Mr. Sanderson, and he chased us out. If he hadn’t been so drunk and hallucinating bats or spiders or whatever, he might even have caught us.”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, it was weird. I heard him trip and when I looked back, he was on the floor with his back up against the wall, hands scrabbling in the air like he was trying to get something off of himself.”

“That was probably the fairies.”

I shook my head. “Right. Tell that to Maxine. She wants to hear all about them.”

“I just think it’s interesting,” she said.

“At least someone has an open mind,” he said, and smiled at her.

It was an open, endearing smile that I hadn’t seen before. It took me a moment to realize why: he could be comfortable with Maxine because he wasn’t trying to impress her the way he was me.

“So you’re really a ghost?” Maxine asked.

He nodded.

“Can I ...?”

She reached out a hand. He lifted his own, and when they should have banged into each other, her hand just went through his. Maxine shivered and pulled her hand back, holding it to her chest.

“That ... that was the strangest sensation,” she said. “Chilly, but kind of, I don’t know, warm and staticky, all at the same time.”

I was impressed with her. I’d never tried touching him myself, but it wasn’t because it made me nervous. I just didn’t want to give Adrian any ideas.

“Well, we should get going

,” I said. “My brother’s band is playing at the Keystone and they’re going to be starting soon.” I waited a beat, then added, “Maybe you want to come?”

Adrian shook his head. “I don’t do well in crowds. I don’t much like it when people walk right through me.”

“No prob. We’ll see you later.”

“Nice meeting you, Maxine,” he said. “I’ll tell you more about the fairies another time.”

Maxine smiled and then we were off, leaving him standing by the hedge while we made our way back to the street.

“So you see what I mean?” I asked when we were out of his hearing range. “There’s nothing really all that spooky about him.”

“Except when you touch him.”

“Yeah, well, that won’t be happening any time soon.”

“But he seemed nice.”

“He is. But he’s also a ghost, so this is never going to be more than a ‘Hi, how’re you doing? Oh, wait, you’re dead’ kind of a relationship. Which suits me just fine, by the way.”

Maxine nodded. “But it’s kind of sad, isn’t it? The way he’s just all by himself like that.”

“You’re forgetting the fairies.”

“Which you don’t believe in.”

I shrugged. “I don’t believe in anything I can’t see for myself.”

* * *

We had a great time at the club. Jared’s band was called the Everlasting First, after a song by some sixties band. They were the middle act, but the best, as far as both Maxine and I were concerned. But then we each had our own reasons to be biased. We left after about the third song of the third band to get Maxine home on time, but not before I got the two of them dancing. As we were going out the door, I glanced back and saw that Jared had this cute, considering look on his face, like he was seeing Maxine for the first time. I told her about it as we walked to her apartment building, and she couldn’t stop talking about him the whole way back.

It made me happy, thinking of my two favorite people as a couple, and I told her so, which just made her beam more.

* * *

So things went swimmingly the rest of the month.

Maxine’s mom kept treating me nicely, even if I showed up looking a little less decorous than I had before our chat at the cafe. I could tell she had to bite her tongue at some of the stuff I wore, but I kept it toned down, even if she didn’t realize it.

Maxine and Jared were kind of circling around each other now, which was sweet and frustrating at the same time. I kept wanting to grab the pair of them and just bang them up against each other.

As for my own romantic front, Jeremy had come back from the camp where he and Pat had been working as counselors, but I now had this other guy, Thomas, interested in me, who was very cool and worked in a used record shop. He kind of reminded me of Frankie, but without the criminal bent, and said I should be fronting a band, which just made Jared laugh.

“It’s all about the attitude,” Thomas argued.

“Oh, she’s got attitude, all right,” Jared said.

Which I guess is kind of a compliment, or at least as much of a one as I’d get from Jared when music and me get mentioned in the same breath.

* * *

Anyway, between the two of us, Maxine and I had pulled off an okay summer. And with the confidence that being Miss Beach Bunny in Florida had instilled in Maxine, I even thought we might have an easier time at school this year.

But then I started having these weird-ass dreams.

It’s funny, but after I learned about Mom’s conversation with Imogene, I got the sense that she thought everything would suddenly be different between us. That we’d become pals instead of just mother and daughter. But I can hardly speak to her at all. My head’s filled with Jared and Ghost and this huge resentment for all the years she’s made me leave the house looking like such a geek. That’s when she even let me leave the house.

How am I supposed to talk about any of that?

And then Imogene tells me about the dreams she’s having, and that totally fills my head. We both agree that Adrian might have something to do with them. I also believe that there might be a connection between her dreams and those fairies of Adrian’s, but she doesn’t even want to discuss that because she doesn’t believe that they exist in the first place.

I can’t explain why I don’t question the idea of fairies like Imogene does. Intellectually—and before I met Adrian—I always knew that they couldn’t exist. Neither could unicorns, vampires, ghosts, talking rabbits, or little spacemen with sleek spaceships and anal probes. But in my heart, I believed. In fairies, at least. Maybe it’s because I had to believe in them. For so long I had to believe in something more than what this world had to offer: my parents’ divorce, the horror that was high school, the loneliness that hung like a shroud over me every day until Imogene stepped up and tore it away.

And that was just when you looked at my sorry little life. When you took in the big picture, the world itself seemed to be falling apart, what with terrorist attacks and wars and weird diseases and poverty and environmental pollution ...

I’d heard about adopted kids who’d have this fantasy that their real parents were going to show up one day and whisk them away to some kind of paradise. I guess my fantasy was that there really were fairies and that, while maybe they wouldn’t whisk me away to Fairyland, at least the idea of something so magical actually existing made everything else more tolerable—don’t ask me why.

I’ve never told Imogene that I truly believed in fairies. I’ve never told anyone, when it comes right down to it, but it’s only odd that I never told Imogene, considering the way her mind works, how it will soar on flights of fancy at the slightest whim, not to mention her relationship with a dead boy. You’d think she’d be the obvious choice.

I’ve even had the perfect opportunity a few times, like when she talks about that Little Bob guy back at her old school and all the stories he had, and then when she introduced me to Adrian. But something holds me back.

I suppose it’s because she so obviously doesn’t believe in them, and my whole life has been pretty much geared to making nice and getting along. I have my small rebellions, but mostly I’ve always done what I’m told to do. By my mother. By my teachers. By anyone bigger and stronger and cooler than me.

I tried to follow suit with Imogene, but she wouldn’t let me. Like the first time she took me to the thrift stores to buy some new clothes. I asked her to pick out what I should get, and she just gave me a funny look. Then she said, “No, you have to choose your own. You have to pick what you want to wear.”

And I had no idea.

But I learned. I learned to the point where, if Imogene didn’t think I should get something I liked, I was brave enough to get it anyway. So maybe I can learn to stand up about fairies, too, except this seems far different from whether or not I should buy a certain top. It feels like it goes deeper, that it taps into the things that really make us who we are, and I don’t know that I want to be different from Imogene in that way. Or maybe what I mean is that I don’t want for her to know we’re that different. But here we are, regardless: me believing, and Imogene with her mind still firmly closed on the issue, even when she’s friends with an honest-to-god ghost.

Mind you, I didn’t grow up believing in fairies—or at least I got huge mixed signals about how I was supposed to feel about them. My dad read me fairy tales and would earnestly explain how they lived in hollow trees and sometimes even behind the wainscoting and under the floorboards, but that didn’t make Mom very happy. She’s always been against any kind of frivolity. Even when I was just a little kid, she argued that I should only experience things I would find useful later on in my academic career.

I know. It sounds horrible. But nothing she’s ever done has been out of meanness or spite. She really, truly wants the best for me. The problem is, she doesn’t think I should get any say in it. She has my whole life mapped out. What she doesn’t see—what she doesn’t want to see—ar

e the uncharted territories that lie inside my head.

I do understand why she is the way she is. She grew up poor, and her parents made her drop out of high school and go to work. Then she met my dad. He was the one who convinced her to finish her schooling and go on to university. She forgets this, how he supported her for all those years. He was so proud of her when she got her degree. Prouder still when she got a job in human resources at Turner Industries, rising rapidly up the corporate chain until she was a vice president. That’s a long haul from the girl who used to work as a waitress in a diner.

Because of how hard her life had been, she was determined to make sure that things were better for me. That I’d be prepared for anything that life had to offer. I was going to learn my manners and dress well and do well in school. Fairy tales weren’t going to be part of my life. Neither were boys, dressing like anything but a geek, having a mind of my own ... Well, you get the picture.

So the pieces of my life that I could live for myself went underground.

The first book I hid from my mom was a copy of Touch and Go: The Collected Stories of Katharine Mully, with those wonderful illustrations by Isabelle Copley. I was shattered when I found out Mully’d killed herself and there were never going to be any more new stories. But I had these and I reread that book until the pages came loose and started to fall out.

They were fairy tales, but set in the here and now, in this city, in Newford, one of them just a few blocks over from where we lived. When I read these stories—like “Junkyard Angel” where the wild girl Cosette disappears in the junkyard, or “The Goatgirl’s Mercedes” with the old crotchety wizard Hempley who’s always trying to steal the goatgirl’s car keys—for days I’d carry around the belief that those kinds of things really could exist. When kids made fun of me at school for the way I was dressed, I’d just go my own way and imagine I had someone like the butterfly girl Enodia waiting for me at home.

From the biographical material in the introduction, I found out about Mully’s artist friend Jilly Coppercorn and totally fell in love with her fairy paintings. I even snuck into one of her gallery shows once when I was supposed to be going to the library, and got to see a whole roomful of originals. I was drunk on those paintings for days and stashed the postcard advertising the show with my growing treasure hoard under the floorboards of my room.

Widdershins

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn