- Home

- Charles de Lint

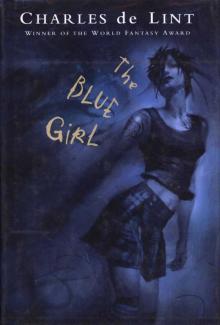

The Blue Girl Page 9

The Blue Girl Read online

Page 9

I was of two minds about the afternoon I’d just spent with Imogene. Happy to have spent it with her, naturally—to have finally had an actual conversation with her without me blathering on like some idiot—but annoyed at how she could be so infuriatingly stubborn about not believing in the fairies. Though, now that I thought of it, maybe talking about the fairies had been blathering on like some idiot—at least it could be construed that way from her point of view. And I guess, to be fair, at first I hadn’t exactly believed in fairies either, not even when I had one standing right in front of me.

I sighed, staring out the door, and watched her walk away, across the scraggly lawn fronting the school and onto the sidewalk running along Grasso Street.

Why was it that whatever I did was the act of the village idiot?

“Had your first tiff?”

Turning, I found Tommery perched on the garbage can across the hall. He lounged like a cat, utterly at ease, as though he’d been there for hours, though I knew there’d been no one on the garbage can a moment ago. There was a big grin on his face, the kind that makes me uneasy around the fairies because I never know if it’s them being friendly, or laughing at me. It’s hard to tell with them. Fairies really are impossible to read. They can laugh at a joke, just like you or I would, but they’ll laugh just as heartily when they’re doing something horribly mean.

So I did what I always did around them and tried to ignore the uneasy feeling that I was the brunt of some joke rather than in on it.

“I guess,” I said. “It just bugs me that she won’t believe me about you—that you’re real. It’s so ridiculous. She’s talking to a ghost, but she still can’t accept the idea that fairies exist as well.”

“Perhaps I could convince her.”

“I don’t know” I was remembering what Imogene had said when I’d told her about how I’d fallen from the school’s rooftop. “You’re not thinking of teaching her how to fly, are you?”

Tommery got this serious, sad look.

“Of course not, Addy. I’d teach her how to see.”

That was exactly what was needed. Once she saw the fairies with her own eyes, like I had, how could she not accept them?

“How will you do it?” I asked.

“It’s a matter of catching her when her minds not so calm. Humans are more open to the hidden world when they’re in a higher emotional state.” I must have looked a little blank. “When they’re very sad,” he went on to explain, “or very happy. Also, when they’ve been drinking or doing drugs— particularly some of the more potent chemical concoctions.”

I tried to get my head around the idea of fairies talking knowledgeably about drugs—it made me wonder: Were there crack fairies? Heroin hobgoblins?—but Tommery was forever surprising me with the depth of his knowledge concerning the human world.

“When it comes to your girlfriend ...” Tommery began.

“Girlfriend! I wish.”

“Yes, well, when it comes to her, I’ve never seen a human with such a level emotional state.”

“She seems animated to me.”

Tommery nodded. “But there’s no inner turmoil. No cracks in the calmness that magic can slip into.”

“So what can you do?”

“Keep an eye on her until the opportunity does appear.”

“I don’t know if she’ll like being followed around.”

Tommery smiled. “But she won’t know, will she? She can’t see us.”

Except I’d know. And I wasn’t sure I liked the idea. I knew for sure that Imogene wouldn’t, considering her remarks about me stalking her. And where would Tommery draw the line? I imagined him checking her out while she was getting undressed or having a shower. Or worse, what if he assigned the job to horny little Quinty?

“Oh, don’t worry, Addy,” Tommery said, as though he could read my mind. “We’re not going to invade her precious privacy. We have our own lives to live and, trust me, they’re far more appealing than the twenty-four-hour surveillance of any human could be. We’ll simply keep an eye on her, check in on her emotional state from time to time. Perhaps send her a dream or two to get her thinking the right way.”

“What about the stuff that Oshtin was saying?” I asked. “He told me that this sight business is something that comes to you naturally, or it’s a gift that needs to be earned. How does that fit in with what you’re planning to do?”

“Both are true. But the ability for us to be seen by humans is also discretionary.”

That took me a moment to work through.

“So you can just appear to her if you want to?” I asked. Tommery nodded. “But it’s better that she discovers us on her own.”

Which wasn’t an answer at all, except that it spoke to some undercurrent that I always sensed around the fairies, but never understood. It was a mystery they played up, some secret with dark edges that I could never see into.

“I don’t get it,” I said. “Why don’t you just show yourself to her and save all the skulking around?”

Tommery shrugged. “We could. It’s just not as ... interesting.”

“Interesting.”

“Exactly. And trust me, her slowly becoming aware of us over time will leave a much more lasting impression.”

“I just want her to know you’re real. That I wasn’t making it up.”

“She will. But if it’s not done right, she’ll forget, and then you’ll be right back where you started.” He cocked his head, giving me a considering look. “The only problem is, doing it this way takes some time. But you can be patient, can’t you?”

I laughed without humor.

“What’s time to me?” I said. “I’m dead.”

Tommery sighed and gave me a slow, sad nod.

“There’s that,” he said.

His voice was soft. If I tried, I could pretend I heard genuine regret in it. I just had to forget the cruel tricks he was capable of, like the year after I died when they gave half the school food poisoning on the last day of classes.

That little incident had the fairies laughing for days.

I didn’t realize how much I’d missed Maxine until she finally got back and showed up at my front door on the first Saturday in August. No, that’s not true. I’d missed her terribly and knew it the whole time she was gone. I’d just tried not to think about it. Maybe I was her first best friend, but she was mine, too. Not having her around to talk to every day was like having a big black hole in the middle of my life, and the postcards she’d sent couldn’t come close to filling it, though I had appreciated them.

I let her talk about the trip. Her dad had rented a condo in Fort Lauderdale, close to the beach, so while he went off to do his meetings and work during the day, Maxine got to turn into a beach bunny. She was, like, totally brown when she got back. It made me feel like I’d spent the month in a basement, but then I don’t tan well anyway.

The important thing was she’d had a great time, and I was glad for her. Nobody had the preconception that she was this loser from Redding High, so they saw her the way I did: cute and smart and funny. She made some friends; she had boys trying to pick her up. Life was good for her. But I noticed she didn’t talk much about the time she’d spent with her dad.

“So,” I said, “are you still thinking of living with your dad for your final year?”

He lived up in the ’burbs, when he wasn’t away on business, but Maxine had assured me that she’d bus in to Redding.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I ... it was a little weird. My dad’s great about not talking about why they got divorced, even though we all know the reason, and he doesn’t dis Mom, either.”

“So what was the problem?”

She shrugged. “I guess just the way he’d look at what I was wearing. He didn’t say anything about how sucky my clothes were—not directly—but I could tell he was worried about me getting to be too much like my mother. ‘It’s okay to be a kid,’ he’d tell me. ‘Everything doesn’t have to be so serious.’ �

�

“But you brought your cool clothes, too, right?”

“Some, but mostly what my mom’s bought for me. I mean, she’d think it was weird if she looked in my closet and it looked like I hadn’t taken anything. And we both know she’d look in my closet—if only to make sure the skirts were still hung separate from the dresses.”

I had to smile. It was sadly true.

“The stuff we got at the thrift stores I wore mostly when I was on my own, at the beach. When my dad was home ... I don’t know. I felt like I’d be betraying Mom if I wore stuff she hadn’t picked out for me. Is that messed up or what?”

I shook my head. “You love them both, even with your mom’s weird quirks. It makes perfect sense. And maybe your mom’s not as tightly wound as we think she is.”

That’s when I told her about the conversation I’d had with her mother.

“You want weird,” I said as I finished up, “how’s that?” Maxine shook her head. “I know exactly what’s going on. It’s because before I left I told her that I was thinking of living with Dad for my final year.”

“But this checking-up-on-me business happened last year, not this summer.”

“So?”

“So her deciding to let us be friends,” I said, “even when she knew my history, happened long before you told her that.”

Maxine looked as puzzled as I’d been that day in the cafe.

“God, you’re right,” she said. “That is weird. Are you sure it was my mom?”

I nodded. “Unless she’s got an identical, nonevil twin.”

“So you can just come over looking however you want?”

“Apparently. But I won’t. I mean, I won’t be all sucky either, but, you know.” I gave her a considering look. “So she didn’t say anything to you when you got back?”

Maxine shook her head.

“Because I told her I’d tell you.”

“I wonder what this means for me?” she said. “Does it mean I can start dressing the way I want and seeing boys and stuff?”

“Only one way to find out.”

I could see the uneasiness rise in her, and she got this shy, nervous look that was so Maxine.

“Oh, I don’t know ...”

“This from the popular beach bunny of Fort Lauderdale?”

“It’s just too strange. Plus, it really makes me kind of mad.”

For Maxine to say she was kind of mad meant that she was furious.

“Don’t go all postal on her,” I said.

“But all these years ... obviously she knew she was messing up, so why couldn’t she just let me be me? I mean, you said she was seeing a therapist about it.”

“You didn’t know that either?”

“I knew she was seeing a therapist, but I thought it was about the breakup with Dad.” She sighed. “How hard would it have been for her to cut her daughter some slack?”

“Obviously, way hard.”

“I guess.” She gave me an unhappy look. “What am I going to do about this? Just walking back into the apartment with her there is going to be so weird, knowing what I know.”

“You want weird?” I asked. “I’ve got way more weird for you.”

And then I told her about finally meeting Adrian, how I’d talked to him three or four times now since she’d been gone. That was enough to put the whole problem with her mother on the back burner.

“Oh, my god! You really met Ghost?”

“Well, it’s not so exciting when you get past the ghost part.”

“That’s easy for you to say.”

“No, it’s true. You know what he looks like, right?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“Well, that’s pretty much what you get. He’s basically just this nerdy guy—smart, nice enough, but he talks like someone who’s read way too many books and doesn’t have any friends. The ghostliness is about all he’s got going for him.”

Typically, Maxine ignored that. “I think he’s got a crush on you. Why else would he have been checking you out all year?”

I laughed. “The crush is big-time. But I don’t know what he thinks’ll come of it. I mean, he’s dead. We couldn’t even touch each other.”

“Would you want to?”

“Not really.”

“Tell me more about the fairies,” Maxine said.

I shrugged. “What’s to tell? I’ve never seen any, though he pretends to. Personally, I think all this talk about fairies and crap—that’s just covering up how messed up he was when he was alive. I’ll bet he stepped off the roof all on his own, and then, when he found he was still stuck here, he made up a story about how fairies had tricked him into thinking he could fly.”

“You think he just made it up?”

“Well, duh, of course. Though you’d think he’d come up with something more plausible.”

“But you said he talks to them.”

“He’s talking to empty space. There’s nothing there. Well, at least nothing I can see. Though I guess to be fair to him, maybe he’s told the story to himself so many times now, he really believes it.”

“But why can’t fairies be real?”

I laughed. “Oh, please. Look, we know he had a shitty life. Only one tiny memoriam in the school yearbook, and while people don’t remember his name, they know Ghost is what’s left over of a kid that everybody ragged on, teachers and students. No, he did this himself, but now he can’t deal with it. And until he deals with it, he’s stuck here, haunting the school.”

“So is that why you keep going to see him?”

“What do you mean?”

“Are you trying to get him to face up to the truth so that he can move on?”

I shook my head. “God, no. It’s none of my business. It’s just that, for all his nerdiness, I still find him interesting to talk to.”

“Even when that talk turns to fairies?”

I smiled. “Even then. Just because I don’t believe in them doesn’t make them uninteresting. Remember, I used to listen to Little Bob’s stories all the time.”

“I’d like to meet him.”

“Who? Little Bob?”

She whacked my arm. “No. Ghost.”

“No problem.”

* * *

But it was.

Maxine called her mother to say she was staying for dinner and that we were going to watch a movie after, which maybe we would, though first we planned to go by the school and then check out Jared’s band, which had an all-ages gig. Dinner was pizza from the place down at the corner, because Mom was at the university. She’d taken this whole going-back-to-school thing very seriously and signed up for summer classes, so we hardly ever saw her. Gino’s didn’t have the best pizza in the neighborhood, but I liked teasing their skateboarder delivery boy.

Over dinner, Jared waxed enthusiastic about the gig, going on and on about the set list and this new tube amp he’d picked up and I don’t know what all. I love him, but that stuff gets old after a while. Maxine was totally interested, though, hanging on his every word, which made me think she’d either developed a jones for sixties music and music gear or a crush on Jared.

We begged off helping the band set up—I mean, I’ve lugged too many amps and then hung around through even more sound checks for it to be a thrill anymore. We let Jared go off on his own, promising to hook up later at the club, and then set off to follow our own agenda.

“So you’re really starting to get into that sixties music, aren’t you?” I said as Maxine and I walked toward the school.

“I guess. It’s fun.”

“Yeah, it is. And so’s Jared.”

She got this cute guilty look. “What do you mean?”

“Well, I think you’re finding him pretty interesting, too.”

“No, I just ... it’s that he’s ...”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I like that you’re into him.”

She looked relieved, but what did she think I was going to do, totally freak out on her or something? Why wouldn’t sh

e be into Jared? I think he’s cool, and I’m his sister.

“So,” Maxine said, “does he ever, you know ...”

“Talk about you?”

She nodded.

“Yeah, but not in a Potential Girlfriend way. But before you get all depressed,” I added as her face fell, “he needs to have you taken out of the Little Sister’s Best Friend context and put into a Potential Girlfriend one.”

“How’s that supposed to happen?”

“You could tell him.”

“God, no. I could never do that.”

I shrugged. “Or I could do it for you.”

“I don’t know. That seems weird.”

“It’s just a day for weirdness,” I said. “And to top it all off, there’s the school, a veritable hotbed of fairies and ghosts. Well, one ghost anyway.”

We stopped across the street and looked at the building. It looked kind of foreboding, hunched there like some deserted warehouse, dark and squat in the fading light. Maxine put a hand on my arm.

“It looks spooky,” she said.

I nodded. “And haunted, too.”

Maxine shot me a worried look, and I had to laugh. “That’s because it is,” I said, and led the way across the street.

As I jimmied the lock to get us in, Maxine was suitably impressed with my break-and-entry skills and full of questions about where I’d learned them. I felt a little guilty as I shrugged them off.

The thing was, I’d still never really talked to Maxine about my old life in Tyson. I’d only told her bits and pieces, the ones that cast me in a good light. I didn’t tell her that I first had sex when I was thirteen. That by the time I was fourteen I’d tried every drug there was to try—which is why I wouldn’t touch any now. That I stood watch when Frankie and the boys broke into houses. That I was the best shoplifter in the gang. Stuff like that.

I had no reason to become the way I did. I hadn’t had a crappy life. But when we moved off the commune and into the city, it was like someone flicked a switch. I just went wild. It started at school, with me reacting to all those smart-ass, cooler-than-thou kids putting me down, and escalated from there.

How could I tell Maxine any of that?

Widdershins

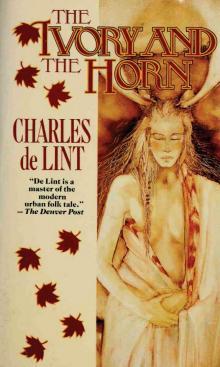

Widdershins The Ivory and the Horn

The Ivory and the Horn Yarrow

Yarrow The Blue Girl

The Blue Girl Spirits in the Wires

Spirits in the Wires The Painted Boy

The Painted Boy The Little Country

The Little Country Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon

Jack of Kinrowan: Jack the Giant-Killer / Drink Down the Moon Moonheart

Moonheart Dreams Underfoot

Dreams Underfoot Into the Green

Into the Green Trader

Trader Spiritwalk

Spiritwalk Someplace to Be Flying

Someplace to Be Flying Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green The Valley of Thunder

The Valley of Thunder Out of This World

Out of This World The Cats of Tanglewood Forest

The Cats of Tanglewood Forest Seven Wild Sisters

Seven Wild Sisters Memory and Dream

Memory and Dream The Very Best of Charles De Lint

The Very Best of Charles De Lint Under My Skin

Under My Skin Forests of the Heart

Forests of the Heart The Newford Stories

The Newford Stories Moonlight and Vines

Moonlight and Vines Angel of Darkness

Angel of Darkness The Onion Girl

The Onion Girl Greenmantle

Greenmantle Waifs And Strays

Waifs And Strays From a Whisper to a Scream

From a Whisper to a Scream Over My Head

Over My Head The Ivory and the Horn n-6

The Ivory and the Horn n-6 Our Lady of the Harbour

Our Lady of the Harbour Dreams Underfoot n-1

Dreams Underfoot n-1 Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1)

Jack the Giant-Killer (Jack of Kinrowan Book 1) Memory and Dream n-5

Memory and Dream n-5 Under My Skin (Wildlings)

Under My Skin (Wildlings) Newford Stories

Newford Stories The Wind in His Heart

The Wind in His Heart Ivory and the Horn

Ivory and the Horn